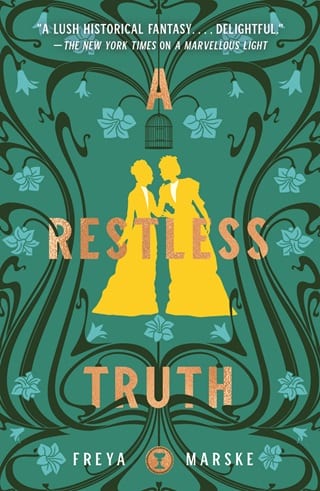

A Restless Truth (The Last Binding #2)

Chapter 1

3%

A Restless Truth (The Last Binding #2)

Chapter 1

3%

1

Elizabeth Navenby was known for three things: needlework, talking to the dead, and an ill temper at the best of times.

These were not the best of times. Seasickness had taken rough shears to the edges of that temper. And being subjected to well-meaning jabber about the stateroom’s furnishings, and how the handkerchief-waving crowds lining the New York docks as the Lyric pulled away looked exactly like a flock of doves—didn’t she agree?—had hardly helped.

So Elizabeth had ordered the talkative Miss Blyth, who had truly disgusting amounts of energy for a girl her age, off to explore the ship.

“Finally,” said Elizabeth to the empty interior of the cabin. “I could do with some quiet.”

It was not truly quiet. But the buzz of the ship’s engines was no more difficult to ignore than the normal noise of a Manhattan afternoon. And the stateroom’s furnishings, now that she turned her attention to them, were… adequately luxurious. If rather modern. Green glass lamps like mildewed snowdrops hung from the brass arms of the chandelier. The chairs were upholstered in a paler green. Dorian’s cage sat upon a low bureau whose drawers had inlaid patterns of tulips with long, looping stems.

“I suppose you’d approve of that, Flora,” said Elizabeth. “You always did like your outdoors to decorate your indoors.”

Another wave of nausea was joined by a dull ache like something had taken her knee between blunt-toothed jaws. Elizabeth had serviceable dry-land knees. They weren’t used to exerting themselves to steady a body against the sea.

She wobbled to sit in the nearest chair and cradled a warmth-spell. The yellow light of it shimmered dimly, reflected in the polished wood of the bureau, then vanished as she applied the magic to her knee. Heat seeped into her bedevilled old joint.

“And I won’t hear a word about how I should be using a stick,” she said.

One of the senior stewards had descended simperingly upon them as soon as they set foot off the gangplank. She’d suspected him of wanting to make calf’s eyes at Miss Blyth, but instead he’d given Elizabeth some damned condescending twaddle about how difficult the crossing could be for the elderly and infirm, and how the White Star Line prided itself on its little comforts for first-class passengers, and if she had any need of extra pillows—some warm broth or ginger tea to soothe her stomach—a walking stick—

At which point Elizabeth had called him an imposing busybody and strode past, leaving Miss Blyth making apologies in her wake. Pointless. Men would never learn to behave if you apologised at them.

“Infirm!” she muttered now. “The cheek .”

“ Cheek, ” said Dorian.

Though it sounded more like cheat, which Elizabeth had taught him to say after she caught that boring old fart Hudson Renner trying to wear wooden rings at her poker table. There was no excuse for using illusions at a civilised gambling party, no matter how much of your fortune you’d frittered away on investments that anyone could have told you were foolhardy bordering on idiotic.

Elizabeth creaked to her feet. Her knee felt better. Her stomach did not.

“I simply didn’t expect to be making voyages in this stage of my life. Though I will allow”—grudgingly—“the last time I crossed the Atlantic, I remember the seasickness being even worse.”

The last time had been in the other direction, when she and her husband left England behind in search of a different life in America. That ship had been far smaller. Nothing like this enormous liner.

Elizabeth snorted in reminiscence. “Poor Ralph. He spent the first day rubbing my back and emptying basins before I was well enough to remember that I had packed one of Sera’s stomach-calming tonics, and that dried chamomile from your garden—”

Grief’s jaws were not blunt of tooth. They snapped shut like a poacher’s trap.

Elizabeth stood with her hand clenched around her silver locket and kept painfully behind her teeth the urge to curse the dead for dying. She wanted to hurl magic at those green lamps for the pleasure of watching something shatter. Memory plagued her, gutted her, snarled at her heels. Flora had wrapped magic like gossamer around her chamomile as it grew. She’d whispered to it until even the flowers’ subtle scent on the edge of a breeze was a soporific charm, like fingers laid on the eyelids.

Slowly Elizabeth’s grip on the locket loosened. She checked her palm, as if she might have pressed the pattern of sunflowers into her skin.

Surely the size of this pain was out of proportion to all reason. She and Flora had spent the latter halves of their lives on different continents. They were old enough that death might well be expected to come knocking.

None of that made any difference to the way Elizabeth had been scooped out, left desolate and raging, when Miss Blyth had first shifted her feet on the carpet and blurted out the news of Flora’s death.

Their age made it worse . It was absurd. Elizabeth was too old to go around avenging murders.

She would do it anyway, of course. Even if her bones felt too brittle to hold the anger that drove her forward.

“I know, I know,” she muttered. “As long as I’ve life, I can choose what to do with it.”

Elizabeth Navenby talked to the dead not in the general, but in the particular.

More than that, she had talked to her particular dead person since long before the descriptor applied. Ever since leaving England, she’d talked as if Flora Sutton were there—as if the locket linked them in more ways than the metaphorical. As if they’d found a way to overcome the limitations of magic at vast distances, and any words she spoke would truly be carried back across the ocean and into Flora’s ears.

She’d refrained in front of Miss Blyth. Her tongue felt crammed full of things that had been building up unsaid. Now that she could let them out in peace, the weightiest ones were rolling forward.

“I thought I would know the exact moment,” said Elizabeth Navenby to her absent dead. “I truly did. I thought—oh, I’d sit up in bed with my heart aflutter. Be stopped in the street by a moment of dread. No—I had to be told to my face, months after you were in the ground. Had to sit there gaping like a fish, and realise that even after—even—nobody thought I might appreciate a damned telegram —”

Another surge of angry grief. As if sensing it, Dorian gave a long croak of a sigh.

No. The wretched bird was not empathetic, merely passive-aggressive; he resorted to the pathos of croaking as a hint that he wanted attention. Or lunch.

Elizabeth removed the bowl from his cage and filled it with fresh water. Hopefully Miss Blyth would remember, during her exploration, to ask the stewards about food for him. Unlikely. The girl was magpie-brained. They’d be lucky if she remembered her way back to the cabin.

“If you were here, you’d be telling me not to trust the girl at all.” A laugh tried to huff its way out. “You always were a paranoid creature, Flora. Never fear. Not a word has passed my lips about my piece of the contract. We don’t tell—not until there are no other options. We promised.”

She replaced the brimming bowl. Dorian nipped her finger in approval as she withdrew.

They’d promised. And yet the paranoid Flora herself had by all accounts given her part of the contract to her unmagical great-nephew—had laid secret-bind on him, sent him to his death, and taken her own life in turn to keep from betraying it—because there were no other options .

Because after all these decades of keeping the Last Contract safe, keeping its three pieces separate and unable to be wrought into a weapon that would pull power from every magician in Britain, a net was closing on the Forsythia Club. On the women who’d been arrogant and curious enough to drag that weapon into the light in the first place.

“Hubris,” said Elizabeth, as if the word were a charm. It tasted bitter on her lips.

She shook herself. Never any point dwelling. Look to the next thing.

Something to quell this nausea, perhaps. She’d sewn a helpful charm into a shawl for a niece suffering a difficult pregnancy—couldn’t recall the exact spell she’d used, now, but piecing it together would be a distraction.

Her sewing kit was in one of the trunks. On her way to rummage, the ship gave a particularly queasy shift. Elizabeth gritted her teeth.

After a few moments she admitted the futility of trying to beat sickness with stubbornness, and went to retch unpleasantly over a basin in the stateroom’s small bathroom.

Someone chose that idyllic moment to knock on the cabin door.

Elizabeth gripped the basin edge and refused to answer. Let them think her asleep. She would not be coddled by stewards. She’d conjure a nest of thorns and hurl herself into it before she accepted an offer of broth . She would deal with this herself.

Once her stomach stopped trying to clamber up the inside of her lower ribs.

The lock clicked. The main door creaked gently open. Miss Blyth, then, already bored with exploring. Elizabeth scowled at the porcelain and waited fatalistically for the flood of bright chatter to resume.

Nothing.

And into the nothing, footsteps. Too heavy to be Miss Blyth’s. Too slow. Cautious .

Alarm flooded in. It managed to shove aside some of the nausea. Elizabeth straightened. The bathroom door, swung ajar, hid her from the main room.

The stunning-spell she prepared was one of Flora’s, built with a single hand and a firm will—leaving the other hand free to hoist a nice solid candlestick, they used to jest, in case the spell missed. Magic filled her palm like snow.

Elizabeth took a deep breath.

She shoved at the bathroom door with her free hand. The damn thing creaked, robbing her of a chance at surprise. A curse slid between her teeth. She had only a brief glimpse—a man, lifting his head sharply from where he was bent over the dresser, pawing through her effects—before she flung the spell at him.

The creak had been enough warning. He dodged. And—oh, hell, he was cradling himself, now. A magician.

She had to try again. Another spell, fast. Blast her stiff old hands. She could hear Flora telling her, as if finally picking up her half of the conversation: You still rely too much on those cradles, Beth, I’ve always said so.

Flora was right. Damn her, Flora was always right. But Elizabeth was bound by her own weaknesses now. The spell struggled to form between her shaking fingers.

I’m sorry, Flora. I did so want to kill them for you.

Her heart shook even more, bounding half out of her chest with fear and fury. It rendered her light-headed and shaken even before the moment when hot-smelling magic sprang from the man’s hands and engulfed her senses like the crash of lightning.

I’m sorry.