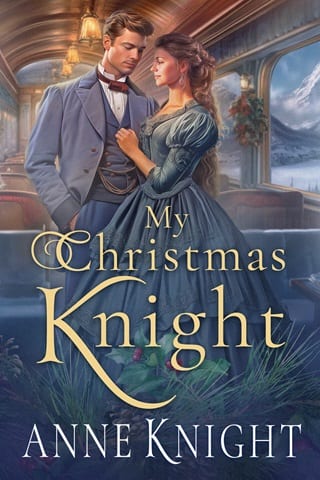

My Christmas Knight (The Fairplace Family #1)

Chapter One

London, December 25, 1856

D ennis Fairplace was very lucky the trains were running on Christmas Day.

He held his pocket watch in his hand, the metal warm from his grip, even as his breath plumed in the frigid air around him. Ten minutes until boarding. He craned his head to peer around the station’s edge to look for any movement. His train, the 12:20 from London, sat ready and waiting right there beside the platform, but they weren’t boarding yet.

Movement down near the back of the train caught his eyes. Men in blue uniforms scrambled around the tracks, gesturing broadly to one another. Slowly a train car came into view, green paint gleaming. A private car being added onto the train.

Dennis rolled his eyes. His departure had better not be delayed because some rich git didn’t want to go slumming with the rest of first class. He glanced down at his watch again, flicking the cover back and forth with his thumb.

He could go back. He could stay and finish out Christmas Day with his family. But no, he’d already paid for his ticket—a whole one pound sixpence—and he couldn’t lose that money now. The ticket agent had scowled at him and growled something about no refunds so close to departure. Dennis tried not to take it personally. He’d be grumpy too if he had to work on Christmas.

His mother was currently grumpy that all of her children weren’t together, that her eldest had left suddenly for Nottingham.

Dennis blinked away images of Christmas candles, pie, pudding, and the green boughs covering their fireplace mantel. He loved and hated it all at once. He’d dreamed of Christmas at home for three years, and now that he’d survived and tried to resume normal life, Christmas felt like a coat that no longer fit. He’d shrugged off the holiday spirit, the carols, even the Christmas tree, and escaped. How could he eat roast beef and spiced mincemeat pie like life was grand when so many good men lay in unmarked graves on the banks of the Black Sea?

Frigid wind swept across the exposed station, sending skirts ruffling and top hats flying from the scant few waiting passengers. His short top hat stayed atop his head.

Dennis tucked his chin into his green wool scarf and winced when the wool caught on the scab forming on his split lip. Another good reason to get away for a while. His mother had been deeply distressed to see his bruised knuckles and split lip at breakfast, likely wondering if the war had made her son a permanently violent man. His brother had wanted to hear about it, certain Dennis was some white knight defending an innocent the night before. His sister had stared at him like he was a stranger.

Sometimes Dennis felt like a stranger. He didn’t know how to explain that to them.

The black train with red trim whistled twice, and white steam poured out of its smokestack. The stench of burning coal filled the station, as did the screeching of wheels. A conductor with brass buttons so shiny they reflected what little light the overcast sky gave off hurried across the platform. He cupped his reddened hands and bellowed, “All aboard!”

The few passengers scurried forward, eager to get out of the wind.

Dennis waited for them to go first. It was cold, but not as bad as a Crimean winter. For a moment his mind flew back to those horrible nights, where the wind whistled through the cracks in tents, a fire was too dangerous in case Russians watched nearby, and cholera spread like a plague. At least it wasn’t snowing. How he hated snow.

I’m not there anymore, he told himself . He’d been back in England for seven months. He should be settling in. Some days he felt like he was. Other days he felt like he was going through the motions, lying to everyone he knew. His head remained somewhere back in a medical tent outside Sevastopol. Maybe his soul, too.

Some fucking knight he was. He still couldn’t believe he’d been given a Victoria Cross and a Crimea Medal by the queen herself. But it was hard to give medals to people buried under the shite and sludge of the battlefields, so they’d given them to Dennis and a few other survivors.

Dennis blew out a breath and tried to focus. England. Great Aunt Astrid. The house. Nottingham.

The passengers, both first and second class, waited in a queue now, except for a couple at the far end of the platform, tucked almost out of sight in an alcove and hidden by pillars.

The woman wore a bland, gray, bell-shaped dress with a wide-brimmed bonnet. It reminded Dennis of his old governess, a bitter middle-aged woman who took out her disappointment in life by rapping his hands at every opportunity.

The man’s golden curls waved in the wind. Tall and athletic, he crowded the young woman’s space. He leaned backward and forward as they spoke as if simultaneously wanting the woman and wanting to leave her. By the way the woman leaned and gestured, she wanted him, too.

This was far more interesting than Dennis’s melancholic memories.

The young man’s greatcoat had a fine tailored cut, likely bespoke. His leather shoes gleamed. The man’s silk top hat had to be eight inches tall. He caught the woman’s hands up and kissed her knuckles, every gesture flamboyant.

The young woman looked over her shoulder, then back at her suitor. Her shoulders curled inward as if hiding. She touched the man’s cheek with her gloved hand, pointing to the private rail car nearby.

He shook his head and motioned to the exit.

Lovers? Dennis shook his head and left his corner, joining the end of the line for car five. It took a moment, but he reached the front and handed his ticket to the porter. Someone slammed into his right shoulder, and he looked over in surprise and frustration.

The dandy with golden hair brushed past, not even apologizing. Dennis frowned as he hurried toward the platform exit. Rude.

“Step aboard, sir,” the porter said wearily, gesturing to the steps. “We leave in a few minutes.”

Dennis brushed off his coat and stepped aboard, searching for compartment seven. All he needed was a nice, long nap. It should be a little less than four hours to Nottingham.

He just needed Christmas Day to end.