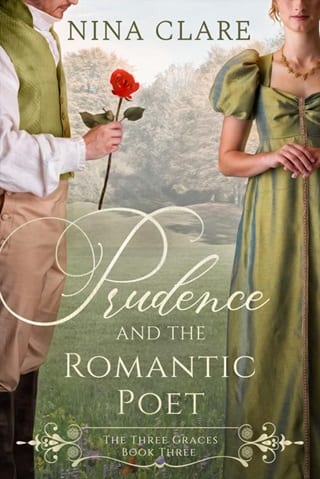

Prudence and the Romantic Poet (The Three Graces #3)

Chapter 1

3%

Prudence and the Romantic Poet (The Three Graces #3)

Chapter 1

3%

1

Bath, England

October 1st, 1819

‘Here we are at last,’ said Prudence, peering out of the carriage window at the elegant stone exterior of Laura Place.

‘How pretty it looks in this light,’ said her sister Constance. The honey-stone houses glowed in the golden light of a late autumn afternoon.

‘I’ll be glad to be out of this carriage,’ groaned Lizzy

‘Welcome back, Mrs Finnistone,’ greeted the butler from the doorway of the house. ‘Welcome, Miss Grace,’ he said with a bow, as Prudence followed her sister inside.

‘Thank you, Mr Hervey,’ said Constance, pulling off her kid gloves. ‘It is good to see you still here. It has been a while.’ She looked about the large entrance hall of the rented town house

‘Two years, ma’am,’ said the butler. He peered beyond the ladies, asking, ‘Is Miss Mercy with you? She was newly tottering about when last we saw her.’ Constance and the butler glanced involuntarily at the spot in the hall where a pair of statues had stood either side of the doorway. The statue of Castor was no more, having been tottered into by a runaway two-year-old. Pollux remained alone; his twin replaced with a Grecian urn.

‘Sadly not,’ said Constance, her voice a little tremulous. It was a source of grief that she had been urged to leave her daughter behind.

‘I trust she is well,’ said the butler, his arms filling with the mistress’s long fur trimmed travelling coat.

‘Very well, thank you. She has just reached four years of age now. And Mrs Hervey?’

‘Hale and hearty, ma’am. Baking pies and tarts and making puddings all day in readiness. She would be here to welcome you, but she’s up to her elbows in flour and dare not leave the spit, for there’s no one to watch it.’

‘How good she is,’ said Constance.

‘There’s only Mrs Hervey and myself, ma’am,’ said the butler, sagging under the addition of a large fur muff. ‘We were not instructed to hire any further staff.’

‘We have a very reliable footman with us,’ said Constance As she spoke, Amos – the footman released by Constance’s godmother into her own family’s employ – came in with the luggage. ‘If you and Mrs Hervey need further staff, please hire them to suit your needs. There will only be my sister and myself until my husband joins us in a few weeks. And I shall not be entertaining, so we shall only require family dinners.’

‘In short, Mr Hervey,’ added Prudence, plucking her sister’s muff from the butler’s arms so the poor man could speak unhindered, ‘We intend to give as little trouble as possible to you and Mrs Hervey.’

‘Perhaps another man for the heavy lifting would be acceptable?’ suggested the butler. ‘Your footman shan’t wish to lift coal and water in livery. ’

‘And you will need a maid to assist Mrs Hervey,’ said Prudence, hanging up her coat on the stand.

‘A little extra help would be appreciated by Mrs Hervey,’ said the butler. ‘A local day girl would suffice.’

‘You and Mrs Hervey must arrange everything as you like,’ said Constance. ‘I will have a talk with Mrs Hervey when she is at liberty tomorrow.’

‘Thank you, ma’am. It is good to have you back.’

‘Are we your best tenants, Mr Hervey?’ said Prudence, trying to tease a smile out of the sober-faced man.

‘By far our favourite persons to wait upon, Miss Grace,’ the butler confessed, but without a smile. ‘I’ll bring tea to the drawing room directly.’

The outriders departed. Tea was drunk. The trunks were unpacked, and dinner was served. The sisters discussed their plans over Mrs Hervey’s chicken pie.

‘I don’t know what I would do without you, dear,’ Constance confessed to her younger sister. ‘I feel so fatigued, I could not have undertaken everything. You made the journey go so smoothly.’

‘Fatigue is perfectly understandable in your condition,’ replied Prudence.

‘But you managed all the packing and the directing at the inns. I could not do the half of it, and it makes me ashamed.’

‘Enough of that kind of talk.’ Prudence served herself a second spoonful of the creamed leeks. ‘Finn would scold you to hear it. You are to be as languid and useless as you choose. It is all to the highest good.’

Constance managed a weak smile and stroked her abdomen which was not yet showing her second child. ‘I am determined to be good,’ she said. ‘Anything to avoid a repeat of my last confinement.’ She gave a little shudder at the remembrance of the long months of bed-bound weakness she had endured. Prudence’s face was also briefly shadowed by the recollection of her sister’s illness before and after little Mercy’s birth. But she spoke cheerfully to dispel the moment of foreboding. ‘Everything will be different this time,’ she said decidedly. ‘We had no notion of your condition the first time, but under Dr Blythe’s care you will avoid all of that.’

‘Yes,’ said Constance, rousing herself to agree with this spirit of optimism. ‘It shall be well. Omni bene , as the doctor likes to say.’ But a sigh soon followed. ‘How I hate being away from home.’

‘It is only for a few weeks, if all is well,’ Prudence reminded her. ‘And we shall have plenty of gentle strolls and the occasional musical concert to entertain ourselves with.’

‘You must not confine yourself to my invalid pace,’ said Constance. ‘You must go to the balls and do all that you desire.’

‘Balls do not tempt me one whit,’ said Prudence.

Constance regarded her sister until Prudence looked up and caught her eye. ‘What are you worrying over now?’ said Prudence. ‘You are forbidden to fret over anything or anyone for the next six and a half months.’

‘I am not fretting,’ said Constance. ‘But I do worry a little over you.’

‘Because I have no desire to go gadding about in ballrooms or to cut a dash in fashionable society,’ said Prudence unconcernedly. ‘Do try these parsnips. Mrs Hervey has a delightful way of braising them in honey and nutmeg. I must ask her for the receipt.’

‘I only wish that you would enjoy yourself more. Meet new people.’

‘Meet eligible young men, is what you mean. Because at twenty-two I am positively on the shelf, am I not? ’

‘Of course not. Though Charity and I were married at your age.’

‘If God intends me to marry, it shall come about in good time. But I have no romantic notions for myself. I am very happy dividing my time between you and Charity. Is that so bad?’

Constance accepted a spoonful of parsnips. ‘Nothing you could do would be bad,’ she said. ‘You are the wisest, most selfless soul on earth.’ She regarded her sister again, her eyes growing a little misty as she said, ‘Mama and Papa would be proud of you.’

‘You always get uncharacteristically sentimental when you are expecting,’ said Prudence. ‘Mama and Papa would be proud of all their children. And it is no credit to be wise and selfless amongst a loving family. I have hardly been tested or tried, have I?’

‘I would not change you for the world,’ said Constance. ‘But I would like to see you try your wings a little. Who knows what you are capable of?’

Prudence did not answer, for the arrival of a rhubarb fool distracted them, and then she deftly steered the subject away from herself, saying, ‘Is the doctor to call tomorrow?’

‘I must write to him to tell him of my arrival,’ said Constance, pulling out of her gown pocket a little case that housed small sheets of notepaper and a pencil. She was fond of lists, and liked to keep them to hand. She read from the list of appointments and duties to be attended to on arrival in Bath. ‘If we are to take the waters in the morning, we shall have to do so early to be back by eleven, for the doctor makes his rounds late morning and will be sure to call. I shall have an interview with Mrs Hervey to arrange menus and the ordering of supplies after luncheon. I will send word to Mrs Smithyman to call upon me, if she is at liberty. I want her to let out some of my gowns and make over some others to allow for my increase . She is so very clever at alterations, and is always glad of the work. Then at four—’

‘By four o’clock,’ interrupted Prudence, ‘you will have done quite enough organising for one day. You are supposed to be resting. I shall arrange the domestic details with Mrs Hervey. Forget rushing out in the morning to take the waters, one day’s delay without those awful glasses of water can hardly set you back. And there is no rush for having your gowns worked over. I will call upon Mrs Smithyman myself and arrange for a convenient time for her to call next week. Nothing need be done tomorrow. We shall rest from our journey. Even the doctor’s visit can wait a day.’

Constance clung to her notecase for a minute, looking ready to argue. But at last she said with some effort, ‘Very well. You are right.’ She crossed off some lines and closed her case with a small snap and a sigh.

‘Good,’ said Prudence.

‘But do agree to go to at least one ball, dear,’ begged Constance. ‘I promised Charity I would persuade you.’

Prudence stifled a rare flash of annoyance, but Constance must have seen the look, for she said, ‘Don’t be cross. Chari was only concerned that it would be all work and no play for you here.’

‘You cannot expect me to go to a ball alone,’ said Prudence.

‘Of course not. But if the Wilsons or Parrys are in town, or if you make any new acquaintance… everyone makes new acquaintance in Bath.’

‘I did not pack a ballgown,’ said Prudence.

Constance looked a little guilty as she said, ‘I asked Lizzy to pack the rose silk. ’

‘That gown is last season’s. It may be very well for country assemblies, but not for Bath.’

‘I was going to have it made over. It needs very little doing to bring it up to fashion. Charity said it only needs the sleeves reset and a ruffle or two at the hem.’

‘You and Charity have had a good long talk over this, I perceive.’

‘Don’t be put out.’

‘I may be the little sister, but I don’t care to be managed.’ Prudence spoke too mildly for her words to be a barb, but she immediately felt a twinge of guilt at expressing her irritation, so she compromised by saying, ‘If I meet with acquaintance and agree to one ball and afterwards decide that I do not wish to attend another, will that silence you and Charity on the subject?’

‘Agreed,’ said Constance, looking relieved. ‘At least one ball, and then Charity cannot scold me for keeping you hidden away like a maiden aunt.’

‘I am a maiden aunt. And there is nothing to be said against it.’ Her sister still looked uncomfortable, so Prudence smoothed things over with the dessert that Mr Hervey brought in. ‘Try a little of this custard,’ she urged. ‘It is silky smooth, just as it ought to be.’

Constance obediently took a spoonful of custard. Her appetite had been diminished for the past weeks. Prudence watched in satisfaction as her sister made a respectable meal, silently blessing Mrs Hervey’s culinary skill. The food was plain by fashionable standards, but it was perfectly cooked and balanced in flavour and texture.

‘Merry-Ann adores custard,’ said Constance sadly, looking down at her empty bowl.

‘I miss her too,’ said Prudence. ‘But though I dote upon her, it would not have been the rest the doctor prescribed were she with with us. ’

‘But it is very hard. It is very unnatural to leave one’s child.’

‘But confess, she is a handful at times. I’m sure I was not half so much trouble at her age, and you certainly were not.’

‘Charity was. Always full of mischief and high spirits.’

‘I have a suspicion her little Alex will be just the same,’ agreed Prudence.

‘How nice it will be if I am carrying a boy. He and Alex will be playmates.’

‘Merry-Ann has very decided opinions on that subject,’ Prudence reminded her. ‘She is determined to have a little sister, and I should not like to be the one to break it to her if she does not get her wish.’

‘She is not the only one with decided opinions on that score,’ said Constance with a note of gloom. ‘Finn’s mother will not forgive me if I do not produce an heir.’

‘Finn does not care a button either way. He only wants a healthy child, and a healthy mother.’

‘But he does need an heir. Or Lindford will go to that cousin of his who is by all accounts abominably lazy, and does not deserve an estate that we have worked so hard to make profitable.’

‘Plenty of time for an heir to come along. At least the abominable cousin has no children of his own to claim the entailment. And if it is not to be,’ Prudence added with a mischievous smile, ‘there is always Charity’s solution to the matter – to despatch the unworthy cousin by imaginative means so that little Alex will be next in line.’

Constance managed half a smile at this nonsensical and murderous solution.

‘ Omni bene ,’ said Prudence, raising her glass of elderflower cordial. ‘Let us determine to make the most of things and have a pleasant time in Bath. ’

‘Agreed,’ said Constance, raising her own glass. ‘After all, this is the most genteel city in all England. It is not as if life can be anything but sedate and pleasant in such a place, is it?’

‘Indeed. Nothing can be less romantic than a month in Bath among a population of valetudinarians. I think we shall be safe from all excitement.’