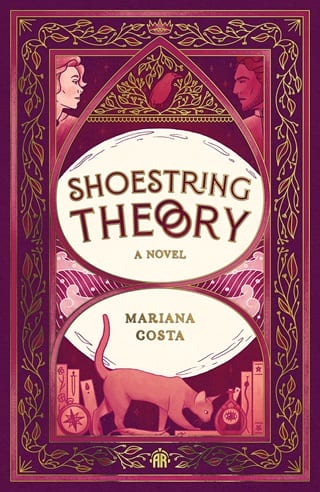

Shoestring Theory

ONE

4%

Shoestring Theory

ONE

4%

Rolling rust-red clouds blanketed the horizon underneath a lightless, lifeless sky. Stepping outside felt as oppressive as experiencing a heatwave, even though it was always tundra-frigid. There was the looming threat of frostbite with every doomed venture outside.

It had been like this for years, enough that the memory of normalcy – weather, food, friendship – was a bittersweet sting in the back of Cyril’s mind.

Most days, he kept to himself. There was little to do in a world so thoroughly destroyed other than sit, be quiet and wait. These things considered, he’d found himself a nice little spot to wait out the imminent end of days. A small cottage by the ocean where a once grassy knoll met sand and sea. Before, when things weren’t quite so bad, he’d thought he might like to retire here. Leave everything behind and plant his bare feet firmly in the damp ocean sand, letting the waves wash away his lingering guilt.

Cyril thought he could pretend there was still some hope to be had in the world, but that was before the sky went black.

Admittedly, it was very hard to ignore the sky going black.

Were he a younger man, he might have called himself plucky. Stubborn as a weed in a rose garden, he’d carved out his own slice of tranquillity in his quaint little cottage. With the little magic he could still force himself to manipulate, he cultivated a vegetable patch which grew the saddest, skinniest tomatoes ever known to man.

When the cold wasn’t so dreadful, he ventured out into the ocean in hiked-up trousers and rolled-up sleeves and spent an hour or two trying to spear whatever wildlife was still resilient enough to make their home in the water. Honestly, he’d gotten quite good at it.

Before, when he went on these little fishing expeditions, he’d need to catch three or four fish, because his familiar, Shoestring, a huge, scraggly, Abyssinian cat who could be mistaken for a malnourished lynx, had, as most real cats do, very particular tastes.

It gave Cyril a sense of purpose, providing for something other than himself. It had made him feel useful for the first time in years. But spending hours wading around in the frigid ocean, dredging it up for any fish that didn’t look too nasty, using up his magic to keep himself from freezing solid while Shoestring watched with his Cheshire-grin of ‘Oh, what shall I do? I’m just a little kitty cat,’ was perhaps the second biggest pain in the arse of his current living situation.

It was a stroke of luck, really, when, in an act of uncharacteristic thoughtfulness, Shoestring crawled underneath an old, underused writing desk and died.

Cyril found out two things that day: the first was that it was possible for the very manifestation of a mages’ soul to crawl under a desk and die with zero physical consequences to the mage themself.

The second was that he was no longer able to cry.

That was a whole month ago, though. Since then, Cyril had discovered a new sense of purpose brewing somewhere deep in his gut (couldn’t be his chest. Not anymore). For a whole week he prepared, digging up ancient wisdom he thought he’d long since forgotten. He even dusted off that writing desk, finally using it for its intended purpose as opposed to a flat surface to take his meals.

By the end of the week, he had a whole diagram drawn up on the floor in chalk and, when that had quickly run out, a congealed mixture of spit and blood. He had positioned Shoestring’s carefully embalmed body somewhere it could always be looking over his work, judging his method just like in the old days. He spoke to himself as he worked, incarnating the cat as best as he could in the absence of the real thing, muttering quips and corrections to himself, doubting his calculations.

It was a very good thing he seemed to be losing his mind, Cyril thought, because then this would all be quite easy.

He needed to be very precise about this whole business, if there was any chance it would end up in anything but a mess on his hardwood floors. Every time he triple-, quadruple-checked his sigils, he darted his eyes to Shoestring, willing the cat to form some posthumous opinion that would reassure him he was on the right track.

Familiars couldn’t speak, of course. At best, Shoestring used to mewl and purr in variations of dis or assent, but Cyril realised he’d come to rely on those infuriating noises like a guiding beacon.

Even after everything, the years he spent in the cottage had never been truly lonely until that stupid, useless cat’s death.

He found himself working faster, eager to get it over with. And if the spell failed, he thought, would that truly be the worst outcome?

Maybe once, a lifetime ago, he could have passed for a powerful mage, the king’s favourite courtier (a gross understatement). But even a powerful mage wouldn’t have been able to undo just how bleak things had gotten. Maybe divine intervention could bring back the blue sky, and the pure weather, and do away with the shadows gathering all around the kingdom, but Cyril had never been particularly devout, and he wasn’t sure any god worth their salt would give him the time of day.

Best case scenario, the gods were eager to rebuild the world from scratch, like a spoiled little lady with her brand-new dollhouse. Maybe they found this all a positive riot. Sure, the rot-spread so far seemed confined to familiar territory, but who could say it wouldn’t seep and fester and poison the entire continent if nothing were done?

No. There was no way to save the world. No way to fix what had been done, when it had gotten this bad.

So Cyril was going to stop it from ever having happened in the first place.

First, though, he was going to die.

Maybe he should’ve felt slightly ashamed of how excited he was by the prospect. It baffled him that he hadn’t thought of it sooner. Not the ritual , of course, that was an act of desperation. A last-ditch effort only a madman could come up with . Cyril was excited for death .

Maybe Shoestring had been tethering him all along. If he died, the cat died with him, and he wasn’t an animal killer . But for years now, Shoestring had been floating through the days, glaze-eyed and sleepy. The fact that Shoestring had had enough and went and found a place to die by himself should’ve been enough of a clue to Cyril that he was doing absolutely no one any favours by staying alive.

But, as he fingered a brassy gold ring looped into a string around his neck, he realised he was scared what might happen if he tried.

Cyril didn’t know how, but he was sure, he was so sure, that as soon as the life left his body, he’d awaken a day later, carefully tucked into a lavish little comforter in a lavish little room, with someone sat on the edge of the bed waiting to greet him.

This would be the outcome no matter how he did it. He might find a way to be drawn and quartered and the pieces would be lovingly stitched together like a favourite stuffed doll. He could drown and new life would be breathed into his lungs just as quickly. He would burn, and… he didn’t want to think about what kind of half-life he’d live after that .

But this was different because Cyril wasn’t throwing his life away. He wasn’t giving up. He was going to right a wrong. And, as he tucked the ring back into his shirt, he felt certain no one could follow him all the way to where he intended to go.

Finally, his sigils were complete. He was satisfied enough with the draftsmanship that there was no need to fiddle with them anymore. His knees creaked from exertion when he stood up to look for a small paring knife from somewhere in his makeshift kitchen.

Cyril was going to die like a sacrificial animal. A long time ago, someone somewhere decided that was how it was meant to be. He was going to be exsanguinated, bleed himself dry until he lost too much to possibly stay upright.

Methodically, he cut diagonals up his arms, starting on his wrists. He was a bit of a coward like that. If he’d gone for the throat, maybe this would all be over much sooner.

As it was, he got to watch the blood pool into the sigils, filling it out and covering it up entirely as the steady stream of red drained from his forearms.

Soon, the blood had slicked the floor so completely he could see his reflection, distorted and ruddied as it was, in the pool. Cyril flinched.

He was under no delusions that he was a handsome man, not even in his youth, but the years of solitude and starvation hadn’t been particularly kind to him. Sharp lines cut and chiselled his face at grim, unhealthy angles. He had always had a somewhat thin frame, but now he was surprised he was still alive at all.

The deep set of his eyes was so dark he could barely see the whites within, especially in dim candlelight, and especially when framed by overgrown, wheat-flaxen fringe obscuring his vision even more.

Cyril scoffed, looking down at his bird-bone wrists. At the end of the day, everything about him was meagre, from his build, to his familiar, to his resolve, all the way down to the tomatoes growing outside his house.

He didn’t think he deserved a sacrificial beast’s death. It seemed too noble. Though his crimes had been overwhelmingly of inaction and neglect, it was difficult to sit and watch someone become a monster without sharing some of that burden. And here, under the gloam of a black sky and a single candle, Cyril looked very much a monster too. A reedy creature from the bowels of the earth, come to snatch children from their beds and grind their bones into fine meal.

Exsanguination, he thought, was a death ill-befitting of Cyril Laverre, disgraced courtier of the king’s inner circle and familiar-less mage.

It was just his luck, then, that his true cause of death was asphyxiation. He drowned gracelessly in his own blood as soon as he fainted face first into the pool he’d been staring at so intently.